One of the ironic and mildly distasteful analogies that Medicine created between food and disease entities ( Strawberry Tongue, Cottage Cheese Discharge, Chocolate Cyst, Miliary Tuberculosis).

However, it does a good job of describing the primary symptom of an epidemic which erupted among thousands of defenseless people. People who were still wandering, shell-shocked, among the after-earthquake ruins of their lives, adding misery and sudden death to injury.

The bacteria’s point of view: the Cholera Vibrio travelled a harrowing road to reach its destination and begin having babies. It came from Asia, in the intestines of human travellers. Expelled, the bacteria had to find their way to water before dying of dehydration. Those Vibrio which survived to reach water needed to remain alive until someone swallowed them. The stomach acid of the drinker would be lethal to most of the Vibrios were it not for the bacterium’s genetic ability to cease protein production and conserve energy during this passage thru the toxic acid environment. The few surviving Vibrio next had to work their way thru the thick mucus of the small intestine to reach the cells of the intestine’s wall. Those who made it activated other genetic mechanisms to begin taking nourishment, and begin protein production again, manufacturing, then excreting an exotoxin. This exotoxin causes the intestine to secrete massive volumes of water and electrolytes (sodium, potassium, chloride, bicarbonate), the vehicle to carry baby Vibrio out into the world.

The patient’s Point of View: gushing out volumes of milky-looking fluid (Rice Water) up to 20 liters a day, the patient rapidly dehydrates and goes into electrolyte imbalance causing profound weakness and muscle cramps. The patients don’t die of overwhelming infection; they die of dehydration. Quickly.

The Epidemiologist’s Point of View: the copious diarrhea, teeming with Vibrio bacteria, contaminate water and food if there is not assiduous separation of drinking water from sewage and scrupulous hygiene among family members and caregivers. Genetic “fingerprinting” could identify the specific strain of Vibrio and probably reveal where it came from.

The clinician’s Point of View: The mortality rate from untreated Cholera is 50 to 60%. Adequate and early treatment can reduce that to less than 1%. And treatment is pretty simple, although intense and exhausting. Just replace the fluids and electrolytes as fast as the exotoxin spews them out. At the volumes we’re talking about, it’s a race.

Here’s a photo of a Cholera bed. The patient lies naked on the plastic-covered mattress, pouring rice-water stool thru the hole in the mattress into a bucket beneath the bed. Measuring the volume of this fluid loss tells you how much electrolyte fluid the patient needs, either orally or by high-volume IV’s. My family first saw this arrangement in Bolivia in 1991. A ship had disgorged ballast water from Asia into the Pacific port of Lima, Peru, bringing the first cholera epidemic since the 19th century to South America. The epidemic spread rapidly, resulting in nearly 10,000 deaths.

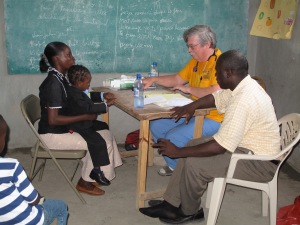

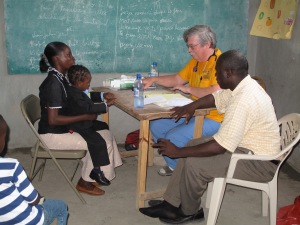

Haiti, 2010: I arrived in Saint Marc, a city sprawled over a plain where the island’s major river, the Artibonite, flows into the Caribbean. The missionaries and I were scheduled to hold multiple clinics in churches, schools and large meeting halls at different communities scattered over the coastal plain where Haitian families grow rice in a desperate attempt to keep starvation from their homes.

The population of St. Marc area had recently swelled with refugees from the destroyed Haitian capital, living in plastic tents strewn over a large area.

Sanitation (sic): the Artibonite River drains the floodplain where families live on small rice plots. It provides water for washing, cooking and drinking, and respite from the heat for playful children.

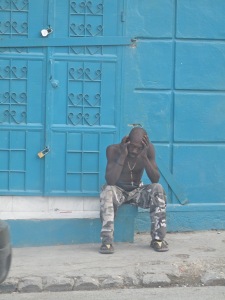

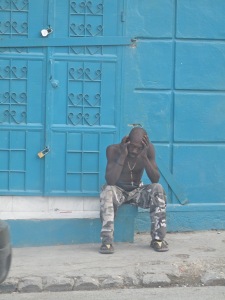

On this half-island country of descendants from slaves who successfully freed themselves, poverty is so profound that it dwarfs what I’ve seen in Bolivia, Mexico, Honduras, Guatemala and Paraguay. Crude outhouses are often too vile or even dangerous to use.

In spite of their extreme and chronic poverty, Haitians are hard-working and classy people. In the clinics we held, nearly every adult and most of the kids arrived smelling of perfumed soap, their hair carefully braided and respectfully soft-spoken.

As we drove from a clinic one afternoon, the silt-laden Artibonite churned, just beyond the van’s right windows. Children, glistening with water, cavorted, splashed and giggled in the brown foam. A woman dipped water from it into a cheap red plastic bowl, then carried the water up to her charcoal cooking stove. A barefoot man walked the bank between the river and the road. Suddenly, he stopped, pulled down his trousers, squatted, and pooped. Finished, he quickly pulled up his pants and continued walking.

The Artibonite would take care of that, too. As soon as it rained again.

The Set-up: multiple Relief agencies had swarmed Haiti after the quake. Doctors Without Borders, Cuban Medical Brigades, Red Cross, Red Crescent, various churches, University of Miami, and the United Nations, among numerous others. As we drove the next day toward another clinic site, closer to the foothills, we passed the U N flag fluttering on a knoll atop a wide slope that flanked the River. Tents and small cabins clustered around the flag.

A few outhouses perched on the slope below.

Rain clouds were building over the mountains that separate Haiti from the Dominican Republic.

The Explosion: In October of 2010, the well respected Medical organization, Partners in Health, began to see patients with severe diarrhea. Physicians there were accustomed to treating gastroenteritis, but these cases were far more severe than they usually see. Within three days, the Emergency Room in St. Marc was overwhelmed with 404 patients (they usually see about 20). Ten percent of them died. Within ten weeks, Cholera was in every province in Haiti. Quickly, the deaths mounted to 100 a day, country-wide. As of this date, 10,000 have died. Haiti’s Cholera epidemic continues.

Epidemiologist, revisited: genetic typing showed this specific strain of Cholera to be unique to Asia. The epicenter of the outbreak was the Artibonite Valley. Shoe-leather epidemiology found leaking sewage from the U N outpost where Peacekeepers from Nepal were stationed.

Yet, for five years, the U N denied that it was responsible for introducing the first Cholera into Haiti in at least 100 years. They (and other politicized agencies) focused instead on Haiti’s horrible sanitary infrastructure and uncontrolled movement of populations following the earthquake. Those conditions certainly did facilitate the rapid spread of the disease (and many other water-borne diseases). A case of Cholera in countries where sewage and drinking water are well separated would not spread very far. But Cholera did not spontaneously generate itself in Haiti.

Once in a Lifetime Opportunity: The U N formally acknowledged its responsibility for the outbreak in mid 2016. Partners in Health, which continues to treat cases, is ready to attack Cholera with a comprehensive Elimination Plan. A project to eliminate Cholera will also control other diseases that have been killing children in Haiti for decades.

With an infrastructure of safe drinking water and appropriate sewage treatment / disposal, not only could they eliminate Cholera, they could dramatically reduce the incidence of other diseases spread by the Fecal-Oral route: childhood diarrhea, Polio, Typoid, Salmonella, Hepatitis, parasites.

PIH has petitioned the U N for funding. So far, commitments from member countries fall short of what’s needed.

What You Can Do:

1. pressure your representative to urge both the U S and U N to see that this Cholera Elimination Plan is adequately funded.

2. donate to Partners in Health. I give to them regularly because the money they receive is well spent. There is no concern of graft or waste.

You must be logged in to post a comment.